In 2002 the Village Newsletter carried a series of articles written by Ron Hence (1924-2004) in collaboration with Sylvia, the magazine editor. They detailed his recollections of life in growing up in Church Lawford in the period between the two World Wars. The articles are reproduced here with minor amendments for context.

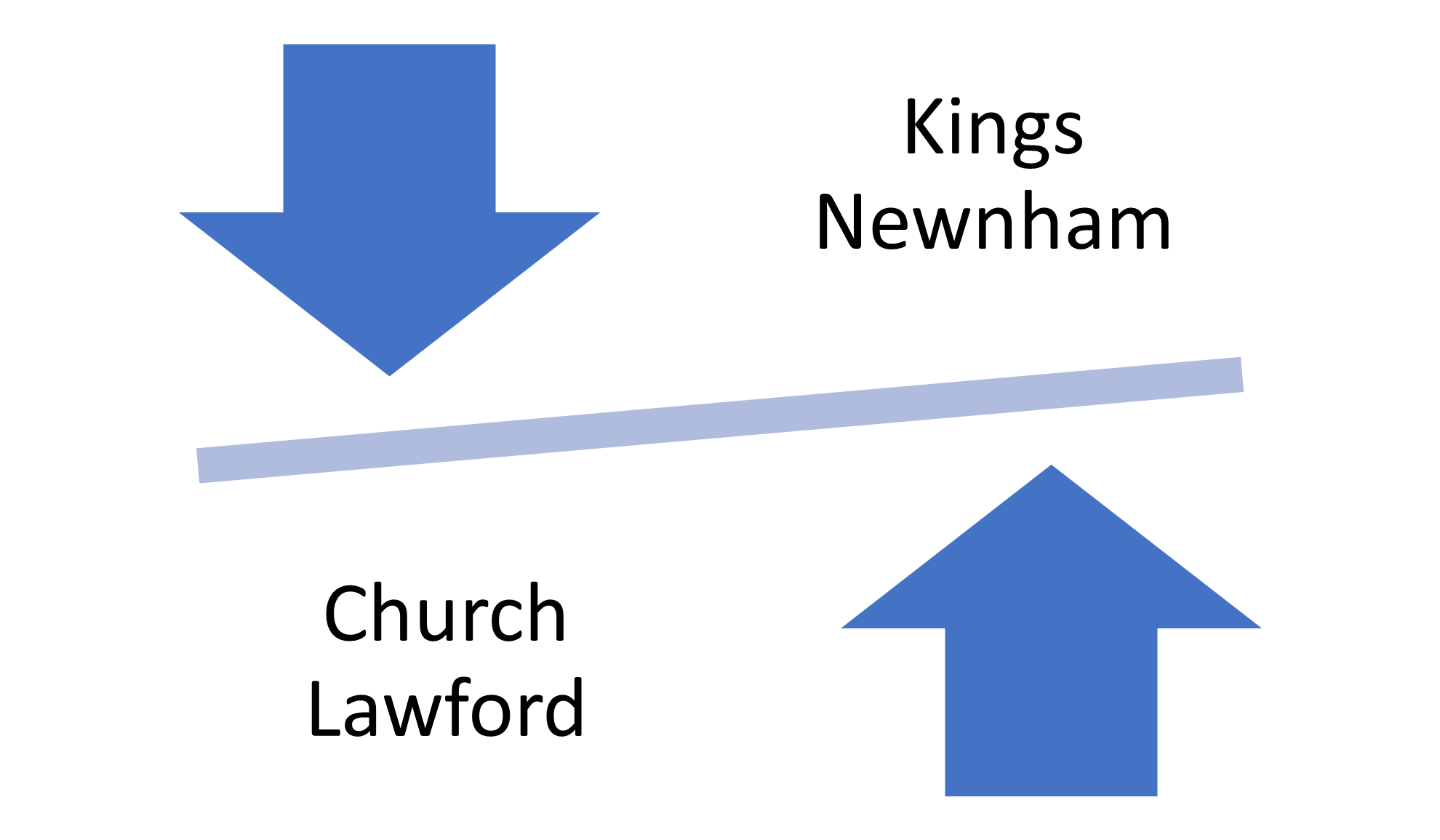

My father and mother were both from local families. My grandparents on my father’s side lived in Long Lawford where my grandfather ran a successful transport and coal delivery business until 1920. My father, the only son in a family of eight daughters, left school at fourteen in 1913 and became apprenticed to the miller at the water mill on the River Avon at King’s Newnham. Each day he walked across the fields from Long Lawford to learn the miller’s trade, grinding the com of local farmers for use as animal feed or for villagers to make bread. Sadly, his apprenticeship was terminated by the outbreak of the 1914-1918 war and he never returned to what was a dying trade on such a small scale.

On my mother’s side, my grandfather, John Pincham, was a Groom and Ploughman at Manor Farm and my grandmother Jane was a cook at the Manor House. After their marriage, they moved into one of the two tied cottages at the White Gate in Church Road, (occupied by Mr. Harris in 2002). My mother was the fourth of nine children, all but one of whom pre-deceased my grandmother, who continued to live in the village until the age of ninety-seven. My mother was also a cook at the Wotherspoon’s farm in Limestone Hall until she married my father in 1920 and set up home in the Schoolhouse where I was born in December 1924.

My recollections of life in the village begin from the late 1920’s and continue through attendance at the village school in the early 1930’s, at Lawrence Sherriff School in Rugby from 1936 to 1941, the early part of the second world war before I joined the RAF on 1 April 1943. My story ends with some observations from brief post-war visits back to the village to see my parents, as I did not live here again until 1982.

Church Lawford in the late 1920s.

What was our village like in the pre-war period from the late 20s to 1939? It was much smaller than it is today, and almost totally involved in agriculture and country pursuits. The village was surrounded by working farms, all using horses as the main source of power for farm implements and all employing local men, (augmented by women and children at peak harvest time), because of the considerable amounts of manual labour required in those days. There was no piped water supply to the village, no gas, no electricity, no sewage disposal, no drainage, no refuse collection and only a few manually operated telephones for the privileged., (the parson, the blacksmith, the postmaster and most farmers all connected to the Wolston operator and used simple numbers like Wolston 56 for Limestone Hall). There was no TV, of course and only cats’ whisker radios using earphones.

The village had its craftsmen: old Arthur Cooke, with a magnificent beard, could make anything in wood from farm carts, cartwheels, furniture, church gates, and bespoke coffins made to measure in a day. My uncle Alf Day, the blacksmith made anything in iron from horseshoes to cartwheel rims, and could repair a full range of horse drawn farm implements either in his ‘shop’ or on site at the farms. There was a village general store run by a Miss Whiteman (located almost opposite the site of the Triangle garage, selling everything from lamp oil to lollipops. The post office was located in the house owned in 2002 by Mr. and Mrs. Howells and provided the full range of postal and telegraph services, (the latter non-existent today, but vital at that time).

We had a full time Rector living in the Rectory, a head teacher and two assistants living in the village, the White Lion Inn and even a roadman to keep the village tidy and carry out minor repairs.

Washing machines were unheard of, and every house and cottage had an outhouse containing a coal fired ‘copper’ boiler for use every Monday. The weekly washday came every week, rain or shine.

Refrigerators were invented, but could not be used without electricity, and everyone had a good-sized pantry with a cold marble slab and terra cotta utensils for the storage of food. Ours was often full of large bowls containing fermenting dandelions or parsnips with a piece of toast floating on top for the yeast as part of the wine making which was a very important hobby activity. At this time, much of our food was produced from the back garden or hedgerow. Many villagers kept pigs and hens. Rabbits were a regular addition to the diet in the days before myxomatosis. Eggs were stored in ising glass; there were swedes, mushrooms in season and blackberries from local hedgerows. Much preserving was carried out by housewives and jam making, fruit bottling, home baking and the salting of meat were high priority tasks especially in the run-up to winter. Cooking and heating was mainly from the kitchen range but there was a village bakehouse located where the British Gas control unit is today and this was still in use for the large Sunday and Christmas joints up to about 1930.

Transportation was poor. There were a few cars in the village and the workshop at the Triangle Garage (now two houses at the top of the village on the main road), had a manually operated petrol pump, (about a shilling a gallon) But for most, transport used on the farms was horse drawn. I can just remember the Carrier’s cart coming into the village on its weekly run from Rugby, but this was soon replaced by the Midland Red bus services which was a boon for villagers for shopping and getting to and from work. At the time, there was still considerable use being made of the railway, which had a station at ‘Brandon and Wolston’ situated on the road past the Brandon Hall Hotel. The railway delivery service was by horse and cart, and there was a village tip at the top of the hill towards Bretford. Villagers made trolleys from a few boards and old pram wheels to take their dustbins to the tip. The amount of refuse was much less then, because garden fires were more frequent and ashes from the home were often used to make or maintain garden paths. Also, there was much less packaging to throw away.

There was a postal delivery service by bicycle from Long Lawford, and the postmaster delivered the telegrams which had been ‘phoned through to him. The Reading Room had been in use for a few years by the late 1920s and the only obvious differences by 2002 are the flushing loos and the absence of two enormous artillery shell cases from the 1914 to 18 war which stood guard each side of the coal fire. These had been presented to the village by the National Savings movement in recognition of the good wartime savings record (I wonder when they disappeared and where they went)? The area surrounding the church is little changed over the years, except that the churchyard was kept to a very high standard and looked much like a public park. The church lighting was by hanging brass oil lamps and heating was by coal fires sunk below floor-level and linked by an underground floor flue to a chimney in the tower. My father, then the verger, would go down to the church at about 2 o’clock on Saturday afternoons in winter, with paper and sticks under his arm. His first job was to clear the ashes from the previous week, load each fire hole with coal carried by buckets from the outside coalhouse, set and light the main fire in the belfry and later take hot coals to start the remaining fires. When all was set, he would return home, only to return about five to stoke up and again about ten to bank the fires for the night. My Uncle Alf had the early duty on Sundays and he would open the fires at 7 a.m. to warm the church for the first services. Compare that with the computer controlled gas heating now in use!

At the corner of Smithy Lane, there was a large market garden leading to a derelict Blacksmith’s shop and Wheatfield Farm with a gate to the field path to King’s Newnham. The five cottages of Smithy Lane were, like much of the village property, except for the school and the Rectory, part of the Duke of Buccleuch’s former estate which was the subject of a large-scale sale in 1918. Nos 2,4 and 6 have now been incorporated into ‘Long House’ but nos. 8 and 10 are much as they were.

Back in School Street, we have house occupied by the Dring’s in 2002. It was then owned by Mr. & Mrs. Beers who had a very large shed in the garden. This had been a pavilion in the 1925 Wembley Exhibition and made a fine workshop. It will figure later in my story when it was put to good use in the second world war. Next we come to the cottages and house owned in 2002 by Mr. and Mrs. Howells and the village post office was housed in a small room on the right of the entrance from the road. Fields and gardens filled the space up to the White Lion Inn, a smaller, thatched version of how it looks today, but it had stables for visiting horses, a ‘spit and sawdust public bar’ for the locals and a lounge bar for visitors. Accommodation and meals were provided for residents as part of the Public House Refreshment Association with an advertisement sign at the top of the village. There was a ‘Jug and Bottle’ department which in those days allowed children to collect a jug of beer. At the rear, there was a fine skittles alley with wooden skittles and cheeses which made a loud crash when thrown.

In Green Lane, there were thatched cottages on the left side with only gardens on the right. My grandmother had the first cottage having moved from the Church Road tied cottage when my grandfather died and my Uncle Jack took over his job and his house at Manor Farm. Turning down Church Road, there was an L-shaped block of cottages on the left and then Jaggards Cottage owned by an eccentric maiden lady, Miss Riley, a fine gardener whose garden and orchard opposite were always a model for the rest of the village.

The village butchers was in Church Road, owned by Mr. Cook and family. He had a smallholding, an abattoir and butchery, but even in those days the place was falling down. He was always in demand for killing local pigs, and walked round the village on Fridays with a large basket on his arm, delivering the weekend joint to his customers. In the next cottages, (where Pam and Bruce Gould lived in 2002), there were two cottages one of which was tenanted by the Dyer family. Mr. Dyer and his son ‘Chum’ were extremely good thatchers, hedgers and ditchers—trades now nearly extinct. Mrs. Dyer was the unofficial village nurse, midwife and confidante of many village ladies about their ailments. She also coped with the task of ‘laying out’ (for those not familiar with the term it is the process of preparing a dead person for the coffin and takes place soon after death). She was an important member of the community; she brought me and quite a number of others into the world and took care of their accidents and illnesses. I well remember her looking after me and mending a crushed finger which had inadvertently been caught in a hay turning machine when the moved during my efforts to realign the chain. The White House was much as it is now, and after that came a block of three cottages now all incorporated into Harford Cottage. Before the end house was built (Mr. Morgan’s house in 2002), the plot was a large garden and yet another blacksmith’s workshop before it moved to its present location at the top of the village. Beyond the white gate was Manor Farm and the Manor House, then owned by Mr. Simeon Robinson, his son Len and his wife. In the late 20s, old Mr. Robinson would require his men to sweep the road from the gate to the church before they ceased work on Saturday evening so that it was clean for the churchgoers on Sunday. This task was a pre-requisite for receiving the week’s wages I believe. Coming back up Church Road, there were two tied cottages already referred to and then, except for a thatched cottage on the site (in 2002) of the Pearson’s house it was fields and cottages all the way to a pair of cottages with a large garden, the village water pump and bakehouse opposite Woodford’s farm.