Rugby-born Compositor and local historian A Edward Treen produced a series of “Half-Holiday Rambles” for the Rugby Advertiser in the early 20th Century. Reproduced here is his essay on Kings Newnham.

Half-Holiday Rambles Around Rugby By A. Edward Treen

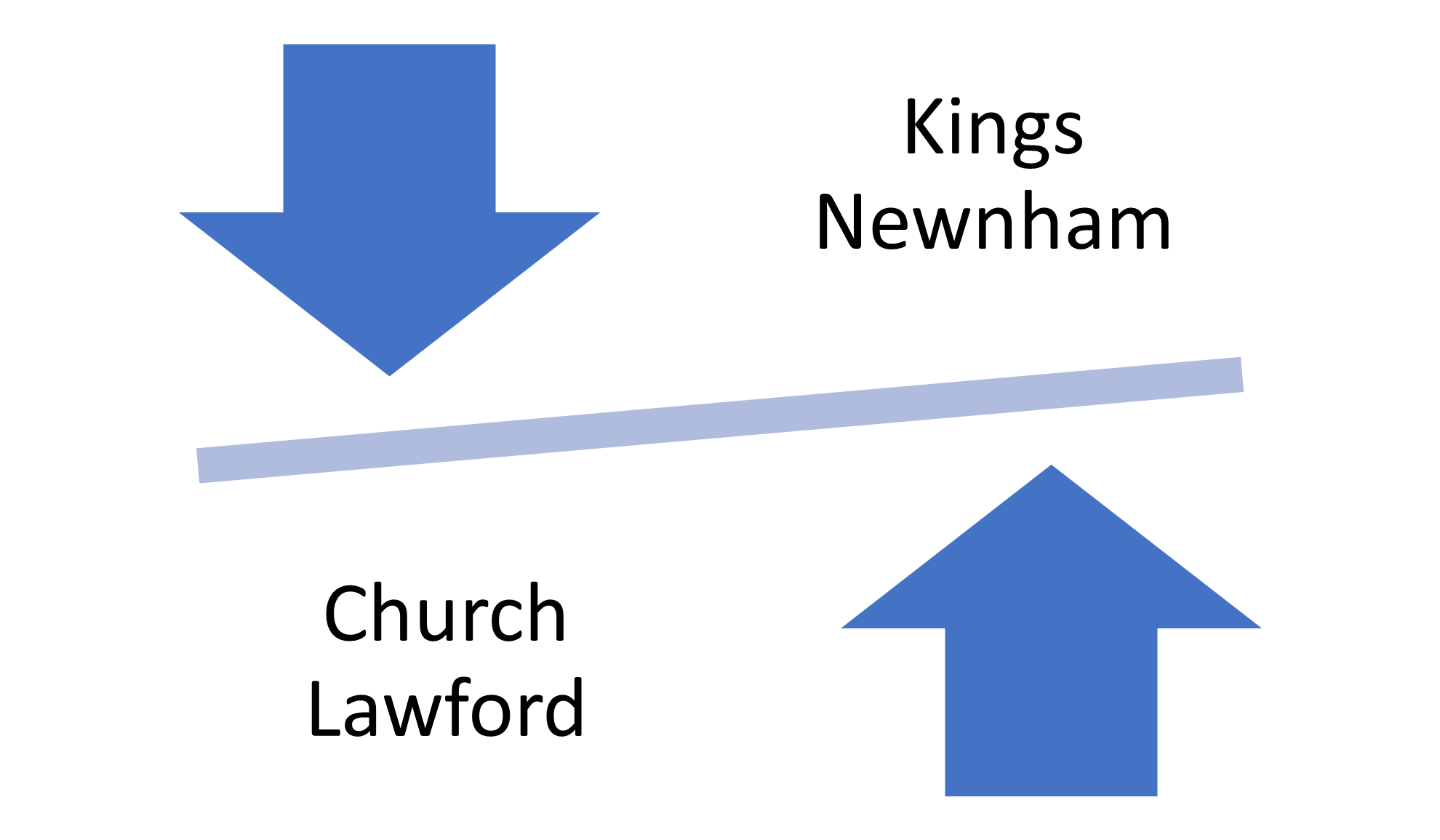

Newnham Regis, or to give it its modern title, Kings Newnham, is a hamlet situated on the bank of the river Avon, about one mile from Church Lawford, to which parish it now belongs, and about four and a quarter miles distant N.W. by W. from Rugby.

8ir William Dugdale, in his Antiquities of Warwickshire, says this place was depopulated in consequence of the enclosure, which ”hath reduced it to a small number of inhabitants, besides the Manor House.” The above learned author, however, does not furnish any date of the enclosure, and in the absence of this important point I am inclined to assign the period when this lamentable occurrence took place to shortly after the Dissolution. On the other hand. Kings Newnham could never have been a place of any great size, as the ancient church, whose dimensions are yet definable, serves to prove; and the place being almost, if not entirely, the property of the Monks previous to the destruction of the Religious Houses through the rapacity of King Henry VIII., I think the period of the decay of this hamlet would coincide with that date.

There is no direct mention of Newnham Regis in the Norman Survey, so we are ignorant of its owner at that period : but Dugdale conjectures that it belonged to Turchill de Warwick, the last Saxon Earl of Warwick, from whom it appears to have passed to Henry de Newburgh, the first Earl of Warwick of the Norman line. It then appears that the land here was held under the above Earl by one Richard (surnames coming into vogue only gradually after the Conquest), who had a son named Hugh, who was a person of great stature and the founder of the Monastery at Wroxhall in Warwickshire. He was succeeded by his son William, who left as heir a daughter, named Margaret, who became the wife of Osbert de Clinton, in which family the Manor of Newnham passed, from whom it descended to her grandchild, Sir Thomas de Clinton, knight.

It appears from the account of the above families in the parishes of Hatton and Wroxhall, that the above Hugh gave and confirmed some portion of the Manor of Newnham to the Canons of Kenilworth in the time of Henry I., this monastery at Kenilworth being founded by Geoffrey de Clinton in 1120. These Canons had special grants from the various members of this family to acquit them of all secular services due to them and their heirs as Lords of the Manor, or to the King; in consideration whereof Geoffrey de Clinton gave to Hugh ten marks of silver; to Margaret, his wife, two ounces of gold ; and to Roger, Earl of Warwick, two gold rings, each having a precious stone therein ; for it was held of the above Earl of Warwick by one knight’s fee, as appears by the confirmation of King Henry II.

It appears that the addition of the name Regis was for the sake of distinction from another Newnham within the same hundred, and in that respect the King was anciently its possessor, as appears by the “Quo warranto” Roll of the 13th year of Edward I., where the King’s Attorney questioned the right of the Prior of Kenilworth to his possessions here, for it was alleged that King Richard I. was seized of the manor. It appears the Canons of Kenilworth substantiated their claim, and they continued to enjoy the rent of this manor until the Dissolution, besides being allowed a Court Leet, Free Warren, and other privileges.

Shortly before the destruction of the Religious Houses we obtain a glimpse of the manor and of its then value. It appears that on the 20th of October in the 17th year of the reign of Henry VIII. the Abbot and Convent of Kenilworth granted a lease to George Dawes and Catherine, his wife, for the term of fifty-one years of all their demesne lands in Newnham, with their pasture called Elthiron, and four closes commonly called Morley’s Close, Bretford Close, Sondepitte Close, and Rollesham Close, together with a mill house, a water mill, and the holme adjoining, with the fishing of their several waters in the Avon ; also their tithe com growing yearly within the Lordship, at the yearly rent of £24 2s. sterling, for the site of the manor and demesne with Elthiron, and the four closes £17 2s., and for the mill house, water mill, holme, and fishery £3, and for the tithe of com £4.

After the suppression of the Religious Houses this manor and its appurtenances psssed into the hands of the King, and was retained by the Crown until the seventh year of Edward VI., when it was granted to John, Duke of Northumberland, and his heirs. However, in the first year of the reign of Queen Mary I., this nobleman suffered death, and his lands wore confiscated to the Crown. The Queen then granted the Manor to Sir Rowland Hill, knight, alderman, and citizen, of London, who shortly after gave them to his niece, the wife of Sir Thomas Leigh, knight and alderman, of London, who became Lord Mayor of that City in the first year of Queen Elizabeth. This Sir Thomas came to reside at Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire, where his descendants have continued to live to the present day. He settled this estate of Newnham on his younger son, Sir William Leigh, knight, and the heirs male of his body. He appears to have lived here. and. according to Dugdale, ”inclosed it,” which I take to mean took in extensive tracks of land to form a park. This event may have been the cause of the depopulation of Newnham. as pointed out by our learned historian, as 1 have quoted in the earlier portion of this narrative. For we read in the accounts of the conflicts during the time of the Civil Wars how the Roundheads destroyed much game and did other serious damage in this park, which acts may have been inspired by some previous acts of tyranny towards the poor agricultural classes by unthoughtful Lords of the Manor.

But to return to the historical narrative. The above-mentioned Sir William Leigh, knight, lived at the Hal! at Newnham Regis, and was here buried on the 7th of May, 1628. He married Frances, daughter of Sir James Harington, knight, of Exton, Rutlandshire. She died, and was buried at Newnham Regis on the 7th of June, 1620. They had three children – Ann, Henry, and Francis. They were succeeded by their youngest son Francis, who lived hero, and was created a Knight of the Bath at the Coronation of James I. He was buried at Newnham Regis on the 2nd of August. 1625. He married, for his first wife. Mary, second daughter of Lord Chancellor Ellesmere; and married secondly, on the 31st of July, 1617, Susannah Banning, widow, at Stepney, Middlesex. Sir Francis Leigh had no children by his second wife, but by his first two sons and one daughter. Alice, the eldest child, married at Newnham Regis on the 27th August, 1618, John Shrimpshere, Esq. George, the eldest son, appears to have died a minor, being buried at Newnham on the 6th December, 1625. The youngest son, named Francis, succeeded to the estate, and was created a Baronet on the 24th of December in the 16th year of the reign of James I. He was afterwards elevated to the dignity of a Baron by the title of Lord Dunsmore on the 31st day of July in the fourth year of the reign of Charles I, after which, for his loyalty and devotion to that monarch in his great distress, he was appointed Captain of the Band of Pensioners, Anno. 1643, and by Letters Patent bearing date at Oxford, on the 3rd day of June, in the twentieth year of the above King’s reign, was advanced to the degree and title of Earl of Chichester, with limitation of that honour to the heirs male of his body : and for default of such issue to Thomas, then Earl of Southampton, and to the heirs male of his body, begotten on Elizabeth, his wife, eldest daughter of him, the said Francis. This worthy married Audrey, eldest daughter of John, Lord Butler or Boteler, of Bramfield, in the county of Hereford. This nobleman resided at the Hall at Newnham Regis, and departing this life upon the 21st of December, 1653 (St. Thomas’ Day), was buried in the Church of Newnham. He appears to have been very popular in his day, and was a great benefactor to this neighbourhood. He obtained Charters for Fairs and Markets for the parish of Dunchurch. He had also granted to him from the Crown the privilege of holding a Court Leet and Court Baron, to be held on his Manor of Newnham Regis, and was appointed Bailiff or Steward of the Hundred of Knightlow, with power to hold a court every three months for the recovery of small debts. This court was not unlike our county courts, and continued to be held until some half-century ago. Many of the other privileges have continued to descend to the present Ducal House of Buccleuch, the living representatives of this Manor. The Earl was a staunch adherent of the Royalist cause, and his park appears to have been the poaching ground for the supporters of the contending party. The soldiers from Coventry frequently came over for that purpose, as appears by the following extract from a diary written by an officer at Coventry :- “ Several of our soldiers, both horse and foots, sallyed out of the City into the Lord Dunsmore’s Parke, and brought from thence great store of venison, and ever since they make it their dayly practise, so that venison is almost as common with us as beef with you.—Friday, August 21th, 1642.”

The above Earl of Chichester was, further, a Trustee of Rugby School, and probably was educated there. His father, Francis Leigh, Esquire (he had not then been knighted), was appointed Trustee in 1602, and he himself, when Sir Francis, by the decree of the Court of Chancery in 1614. He left issue only two daughters, Elizabeth and Mary. The younger, Mary, became the wile of George Villers, Viscount Grandison. The daughter Elizabeth married Thomas, Earl of Southampton, and to children of this union the titles and honour of the Earl of Chichester descended, as was expressed it should do so by the term of the patent of nobility. This Elizabeth and her husband had four daughters, but no son. Three of these dying young, they were succeeded by their eldest daughter, Elizabeth, who was twice married – first to Joceline, Earl of Northumberland, and by him had issue only one daughter, who married the Duke of Somerset. She married, secondly, Ralphe, son and heir to Edward, Lord Montagu, of Boughton, Northamptonshire, who, in the first year of the reign of King William and Queen Mary, was created Viscount Monthermer and Earl of Montagu, and in the fourth year of Queen Ann was further advanced to the title and dignity of Marquis of Monthermer and Duke of Montagu. He only lived to enjoy his new dignity three years. He was interred in Warkton Church, Northamptonshire, but there is no monument or tablet to his memory. He contracted the habit of marrying widows. During his visit to France as an Ambassador he formed an attachment for the above Elizabeth, who was then the widow of the 11th Earl of Northumberland. Evelyn calls her the “most beautiful Countess of Northumberland.” She died in 1690, and is said to have been buried at Warkton. By the Duke of Montagu the above Elizabeth had four children—Ralphe, Winwood, John, and one daughter named Anne. Ralphe died at the age of 12 years. Winwood died at Hanover, aged about 20 years of age, and John succeeded his father. The Duke died on the 9th of March, 1709, and his only surviving son, John, succeeded to the honours and estates, which included property at Dunchurch, Cawston, Church Lawford, and Newham, besides extensive possessions in Northamptonshire. His son John, Duke of Montagu, who became the Lord of Newnham Regis, is one of the most interesting figures in the history of his family. He married Lady Mary Churchill, fourth and youngest daughter and coheir of John, the celebrated Duke of Marlborough. Shortly after he came into the estates of his family he purchased other adjoining lordships, including the Manor of Geddington, Northamptonshire, and made extensive improvements in the park and grounds attached to Boughton House in that county. In this district he carried on much the same work. To his love of tree-planting we owe that matchless avenue of Scotch firs and elms on the London Road. He was named “John the Planter,’ and to this day the thousands of noble trees around Boughton House add such dignity to the venerable pile that it ranks among the most impressive of the stately homes of England. But beyond his profound reverence for beautiful trees this Duke has bequeathed to posterity the record of a most amiable and charitable disposition.

The following anecdote, which exhibits the blending of these two qualities, is so instructive and interesting that I trust I may be pardoned for introducing it to the notice of the reader:`

“Shortly after the declaration of peace he noticed a middle-aged gentleman, clad in a worn and shabby military suit, walking to and fro in the Mall, or seated in a mournful and dejected attitude upon one of the benches there. His curiosity being excited, he caused secret inquiries to be made about him, and found he was an officer who had served with bravery and distinction in the late wat, and having been discharged on half-pay. Having no other source of income, he had been obliged to send his wife and family to her friends in Yorkshire, regularly remitting them half his pay, while he remained in town seeking employment. The Duke having made all his arrangements, sent one of his people to him as he sat one day in his usual melancholy attitude in the park, and desired him to do him the honour of dining with him the next day. The Duke stood at some distance to watch the effect of his message, and enjoyed the expression of astonishment with which he saw it was received. The invitation being accepted, at the time appointment the Duke received the officer with every mark of respect, and told him that he had ventured to ask the favour of his company in order to oblige a lady who had long entertained a sentiment of admiration for him, and added that she was in the next room. The officer at first showed some resentment, but on the Duke declaring that both he and the lady wore actuated only by sentiments of honour in arranging that interview, he was prevailed upon to enter the room, and we may imagine his feelings on finding there his wife and children, whom the Duke had privately sent for from Yorkshire. After dinner the Duke presented the officer with a deed granting him an ample annuity for life.”

It will be admitted, I think, that such deeds as these should live. Too often we bury the good deeds of men with their bones, and the evil that they do we speak of after. Let us rather emulate the good, and show that past, as well as living, members of the peerage have been our greatest benefactors.

Portraits of this Duke and of his Duchess Mary are among the priceless pictures in Boughton House, and an engraving of this worthy is given in Mr. R. T. Simpson’s interesting booklet on “The Wroth Payment at Knightlow.”

The above noble Duke and his Duchess are interred in Warkton Church, and magnificent monuments are erected to their memory, which I described some years ago in this journal. They were succeeded by their only surviving daughter, Elizabeth, who married Henry, the third Duke of Buccleuch, and thus became the great grandmother of the present noble and kind-hearted Duke of Buccleuch, who, with his eldest son, the Earl of Dalkeith, are the living owners of the lordship of Newnham Regis.

NEWNHAM REGIS BATHS.

This parish was for many generations been famous for its baths, but during recent years they have passed out of repute. In former times there was an ancient “ holy well ” situated here, once celebrated for the cure of various disorders, but this has long passed away. The bath yet remains, hut is now seldom or never used. The water which supplies the bath is considered a weak chalybeate, and issues from a mineral spring about a mile distant, passing, in its course to the bath, through a lime pit. This water was in request by previous generations, but, I believe, is not used now. It was always found to be very efficacious in scorbutic complaints and in the healing of flush wounds.

Thus I have discoursed somewhat diffusely upon a very interesting parish, judged from an archaeological point of view, and hope it will be the means of showing the important part which many of the former residents of these village have played in the historic annals of England.