The Geology of the local area, notably between Kings Newnham and Little Lawford, based on clay and Blue Lias limestone has resulting in the area having a number of historical notes, regarding the Baths, the Lime Works and the archaeological findings.

The baths at Kings Newnham were said (in 1921) by well-known local historian Emily Robinson L.L.A. to be of Roman origin, and remains of old Roman brickwork were still in existence. They did come into prominence until the reign of Queen Elizabeth, who, as a princess, visited Lawford Hall. This recorded that in 1575 the wonderful healing properties of the spring were discovered by a labouring man named Clement Davies, who wounded his hand when cutting down a tree. He bathed his arm in the spring and, to the surprise of everyone, it was cured in a week. The sensation of this wonderful cure reached the ears of Queen Elizabeth, who sent her chief physician down to investigate. He reported that the water, among other things, was good for rheumatism and dyspepsia but “not” more than eight pints a day” were to be taken.

Further reference to the baths were in the 1795 publication by Samuel Ireland which looked at settlements on the Warwickshire Avan, as discussed here. He maps the course of the waters from spring to well, and also suggests that local roads inhibited the popularity of the waters.

The wells had been mentioned by several celebrities in the 17th and 18th centuries, and in 1815 (says Dr. Buckland) “two magnificent heads . and other bones of the Siberian rhinoceros and many large tusks and teeth of elephants, with some stags’ horns and bones of the ox and the horse were found in a bed of diluvium.” The baths were in use until the last century, a large one for swimming, small one for hot water bath, and a light foot bath. The dressing-rooms were converted into living rooms, whilst in the parlour the following inscription is to be seen on a pane of glass: “Rev. Edward Nason, M.A., Curate of Brinklow, August 15th.1784” They were in the possession of Lady Jane Scott. who composed the tune for the famous -song “Annie Laurie. “ Her husband Lord John Scott had restored the baths in 1857, and following his death three year later his wife kept the facility open for a while.

More details on the 1815 finding by Dr Buckland are documented in the 1850 business directory for the area :

“two magnificent heads and other bones of the Siberian rhinoceros, and many large tusks and teeth of elephants, with some stags’ horns, and bones of the ox and horse, were found in a bed of diluvium, which is immediately incumbent on stratified beds of lias, and is composed of a mixture of various pebbles, sand, and clay, in the lower regions of which, where the clay predominates, the bones are found at the depth of fifteen feet from the surface. They are not in the least degree mineralised, and have lost almost nothing of their weight or animal matter. One of these heads, measuring in length 2 feet 6 inches, together with a small tusk and molar tooth of an elephant, have been deposited in the Radcliffe Library at Oxford. The other large head has been presented to the Geological Society at London.”

The baths were also referenced by local researcher Liz Parvin in her 2014 articles on Kings Newnham for the village magazine – here.

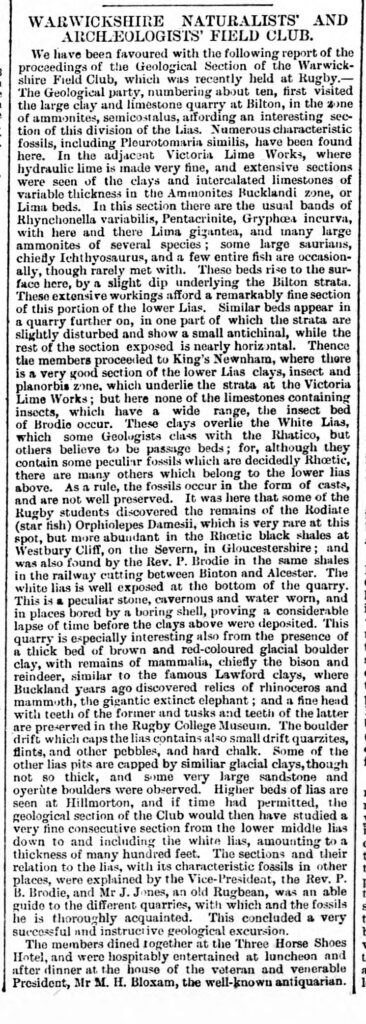

Further findings regarding the geology and archaeological findings in the area were revealed in 1883 when the Warwickshire Naturalists and Archeologicalists’ Field Club visited the area, as discussed in an article in the Leamington Courier of 1st September 1883.

The observations of Emily Robinson were corroborated some thirty years later, in 1953, when a report by F W Shotton looked at local Pleistocene Deposits – notably in Kings Newnham. The Report was published as part of the “Philosophical Transactions Of The Royal Society Of London” entitled “The Pleistocene Deposits Of The Area Between Coventry, Rugby And Leamington And Their Bearing Upon The Topographic Development Of The Midlands”

The salient section was thus :

d) Pre- Wolston clay deposits at Kings Newnham and Little Lawford Examination of figure 9, will show that there is a patch of sandy deposit existing north-east of Kings Newnham ( ca. 465780), which, though it is separated from other outcrops of Baginton sand, is in the same position as the latter in relation to the Wolston clay. Although it has at its base up to 3 ft. of gravel, it is in all not more than 9 ft. thick, and so I have indicated both sand and gravel by the Baginton sand symbol. The Geological Survey shows the edge of this deposit on Sheet 169, but on its unpublished ‘ 6 in.’ sheet which extends farther south, gives it much too great an extent by joining the outcrop to the flint-bearing terrace gravels (No. 2) which lie west of Little Lawford. It is not of great significance whether the basal gravel is equivalent in age to part of the Lillington and Baginton gravels as well as to the Baginton sand, for it is clearly older than the Wolston clay.

The real importance of the deposit is that it yielded, about 130 years ago, the great series of mammal remains described by Buckland (1823), Guvier (1822) and Owen (1846). These are the specimens usually noted in literature as coming from ‘Lawford, near Rugby’, and it is first necessary to prove that they came from the outcrop in question and, in more detail, from the overburden of an old pit in the Lias which still exists, though it is half flooded and partly filled by tip, at M.R. 465777, adjacent to the farm Fennis Fields. This pit must once have been an exceedingly large working in the Lower Lias. The worked area covers about 10 acres and its depth must have been considerable for, at the north end, there is still over 20 ft. of face above deep flood water. There is, moreover, a shaft presumably leading to underground workings in the White Lias, and the activity was sufficient to justify the construction of more than half a mile of canal leading as an arm from the Oxford Canal to a loading wharf. These facts indicate that it was by far the largest of the now disused Lias pits of the district, and also suggest that its heyday of activity was in pre-railway times. It lies in the parish of Kings Newnham, but the stream which forms the eastern boundary of the pit and has broken into it, is the parish boundary. It is thus actually 0.88 mile from Kings Newnham village, but only 0.39 mile from Little Lawford, 1.08 miles from Long Lawford and 1.7 miles from Church Lawford. Workers from Rugby would never touch Kings Newnham but would leave the road at Little Lawford to take a path leading to the quarry. It is therefore not surprising that the locality became spoken of as ‘Lawford’, and all the mammal remains in the Oxford geological museum and most in Warwick Museum carry this label.

Fortunately Buckland, in his Reliquae diluvianae (1823), leaves no doubt about the origin of the actual specimens now at Oxford, for although he on at least two occasions gives Lawford as the locality, his only detailed reference runs as follows (p. 176): ‘At Newnham, in Warwickshire, near Church Lawford, about 2 miles west of Rugby, two magnificent heads and other bones of the Siberian rhinoceros and many large tusks and teeth of elephants, with some stag’s horns, and bones of the ox and horse, were found in the year 1815, in a bed of diluvium, which is immediately incumbent on stratified beds of lias, and is composed of a mixture of various pebbles, sand, and clay; in the lower regions of which (where the clay predominates) the bones are found at the depth of 15 feet from the surface.’ As the pit under discussion is the only one in Kings Newnham parish, or indeed anywhere near, which has something like 15 ft. of superficial deposits above the Lias, it alone can be the source of the bones. Additional confirmation is given by Cuvier (1822), who, in his reference to bones of Rhinoceros and Elephas respectively, speaks of ‘Newnham, near Rugby’; by two humeri of Rhinoceros in Warwick Museum (G624 and 625), which, unlike the other vaguely labelled bones, carry the inscription ‘Newnham lime quarries, Warwickshire, 15ft. below surface’; and by the rhinoceros head in the library of the Geological Society, mentioned by Buckland and labelled as presented by him in 1820, from Kings Newnham, Church Lawford, Warwickshire. 218 F. W. SHOTTON ON THE PLEISTOCENE DEPOSITS OF THE The most complete section now visible in the pit is as follows: (a) Clay top obscured by slip (b) Orange sand ic) Clayey gravel with fragments of ironstone, Lias limestone and Bunter pebbles 4 ft. 7 | ft. ft (Wolston clay) (Baginton sand) (Baginton sand or Baginton-Lillington gravel) Total of drift (d) Lias clay, seen to 13 ft. 9 ft. Another section, farther round the pit, shows a very coarse deposit of local angular blocks at the base of the drift, as follows: (a) Pebbly sandy clay 3 ft. (Wolston clay) (b) Red sand 4 ft, (Baginton sand) (c) Sandy gravel with small pebbles of Lias and 2 ft. Bunter l (baginton sand or (d) Coarse gravel, with large angular blocks of 1 ft. J Baginton-Lillington gravel) Lias limestone in coarse yellow sand (e) Lias clay, seen to 10 ft. These sections, particularly the first, closely conform to Buckland’s description, and as a final confirmation there is with the large series of remains in the Oxford museum a sample of ‘sand from the Elephant Bed’. It is a ferruginous sand mixed with much Lias clay, containing a Bunter pebble, a fragment of a belemnite and another of Ostrea and many bits of compact grey Lias limestone, and is identical with bed (c) of the first section above. Exactly similar material also fills cavities in a lower jaw of Rhinoceros in Warwick Museum.

In 1973 the Rugby Archaeological Group summarised the previous findings in the King’s Newnham Area, alongside details of a 1962 dig in the Church Lawford area – details here.