In 2018 Village Historian Frank Hartley compiled a series of articles for the Village Magazine to bring together stories from the Villages past relating to the current month. This is the March version.

As befits a month which marks the transition from winter to spring, the month of March traditionally, “comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb”. The weather, however, is often too changeable and varied to conform to any such maxim. In keeping with the nature of this mercurial month I have dipped into the archives of Church Lawford’s history and pulled out a few stories from our village’s past which have one thing in common; they all took place here, in in the place in which we live, in the month of March.

Our first visit takes us back to the March of 1789 where the country is celebrating the return to health of his Majesty King George III who had been seriously ill since the previous October suffering both physical impairment and mental instability. (The nature of his condition is still very much in dispute – medical opinion is currently divided between those who argue for the hereditary disease of porphyria and those who favour a form of bi-polar disorder). His timely recovery averted a serious constitutional crisis over the powers which George, Prince of Wales, as Regent, would exercise. (The Prince strongly supported the opposition Whig party led by Fox against the Government of William Pitt, and the latter may well have had to resign). A celebratory event took place locally at Dunchurch, on Tuesday 17th of March which we know was attended by a Mr Dalton, farmer of Church Lawford, along with, no doubt, many others who joined in the general rejoicing. The main feature of the event was the “Illuminations” (all supplied by candle -power). There probably would have been fireworks too, perhaps in keeping with a village where the Gunpowder Plot conspirators had waited for news of Guy Fawkes’ attempt at pyrotechnics in London. Unfortunately for Farmer Dalton (we are not told his Christian name), “his Horse took Fright at the extraordinary Light, threw him and afterwards dragged him a considerable Distance by the Stirrup; by which Accident he is much hurt …and is now past all Hopes of Recovery”. Perhaps the Northampton Mercury was being unduly pessimistic for there is no burial of an adult male Dalton recorded in the Church Lawford Parish Records for 1789 and none until March 1792 when Edward Dalton is buried. This may, or may not, be our luckless horseman. There were a number of Dalton families in the village at the time, including one at Limestone Hall and it may take some time to narrow down.

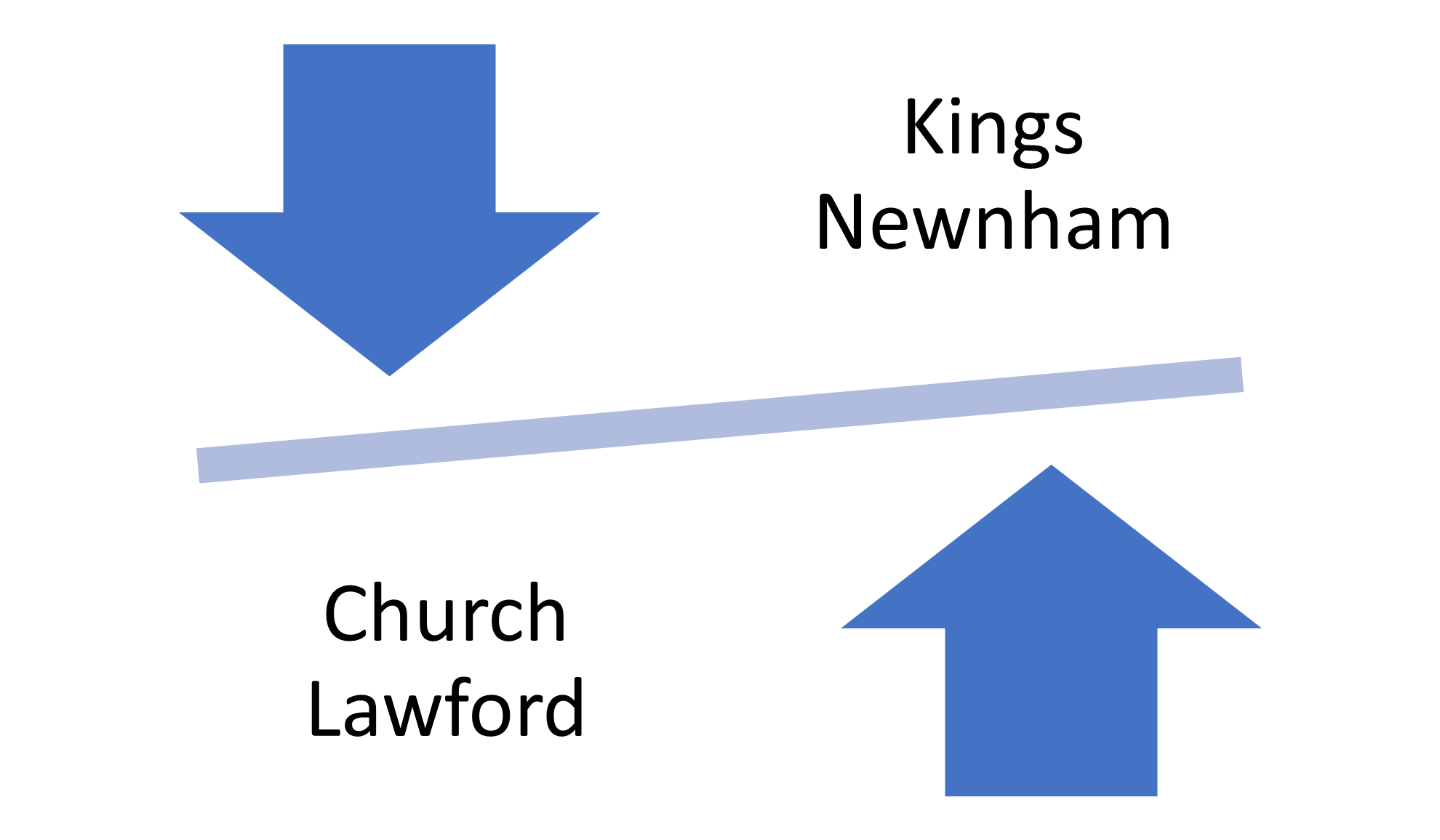

On a brighter note, on the first day of spring 1893, the village “was all astir to witness the marriage of Fanny, youngest daughter of Mrs Clarke of King’s Newnham, with Dennis, second son of Samuel Clarke of Cathiron. The bride looked very nice in a costume of white crepon, tulle veil and orange blossom. Upwards of 30 relatives and friends sat down to breakfast, and the bells rang merrily at intervals during the day, the ringers being afterwards entertained to supper at the bride’s home.” The service was taken by the Rector, Rev William Manners Wood, who was shortly afterwards to leave the village. Both bride and groom were 21 years of age and came from farming stock and were to farm for many years at Harborough Magna. Dennis and Fanny were good servants of this village. Dennis did a long stint as Churchwarden and Fanny was active in the church. They both died in 1950 and are buried in a grave close to the rear gate of the churchyard.

Our Victorian forbears were very much alive to the problems caused by drunkenness amongst the working population. A number of Temperance Societies sprung up in the mid to late Victorian years, notably the Band of Hope. The Church of England Temperance Society (CETS) was set up in 1862 and was active in most towns and villages, including Church Lawford. The village branch of CETS held monthly meetings at some of which there were musical recitals. At the well-attended meeting held in the schoolroom on 9th March 1891 attendees would have heard inter alia, a “pianoforte solo” by the indefatigable Miss Alice Worth Townsend of King’s Newnham who also played the organ at Fanny Clarke’s wedding, a reading by the Rector (Rev Manners Wood) of “Mexican Plug”, from an account about an unruly horse by Mark Twain and a “vocal duet” of the old song, “Gypsy Countess” by Miss Smith and Miss Whiteman. The last named performer I believe to be Isabella Whiteman, daughter of Charles, the local blacksmith.

A tragic case which is perhaps illustrative of the environment in which the Temperance Movement operated and, like Mr Dalton’s case above, points up the perils of transport by horse, is reported in the Coventry Standard of the 24th of March 1865. An Inquest into the death of Edward Hunt (15) was held at the White Lion on 22 March by the Coroner W S Poole in front of a jury made up of farmers. It appears that Edward was the son of William Hunt, farm labourer, and his wife Sarah nee Burnham; in 1861 he had six siblings. We must restrict ourselves to a brief summary of the facts. Evidence was given by “Mr H Brierley, a farmer of King’s Newnham”. In fact there were two Harry Brierlys, father and son farming at Newnham Hall; the witness at the Inquest would be the son, aged 30. Mr Brierley instructed an employee, Joseph Spencer, to take a “four-wheeled wagon” and a team of three with “a load of oats” to Cawston and to R Pennington at Rugby. Joseph, a widower, lived with his two daughters and one son in King’s Newnham where he is recorded in 1861 as working as a wagoner. He was expected to return with the wagon by about 4pm. Mr Spencer took young Edward with him. Edward had “driven the harvest team last year”. At about 3:30 pm Mr Spencer was observed, by W Amos, “a cow boy to a Mr T Bromwich of Wolston”, “leaving the Royal Oak beer house at New Bilton. {Edward} stood by the side of the horses”. This would be William Amos of Wolston (aged 17 at the time. Young William observed that the wagon was empty and it is thus clear that the delivery of the oats had been made. He also observed that, “Spencer was tipsy as he came out of the beer house and staggered in his walk”. It appears that William was given a lift and while he and Mr Spencer sat in the back of the wagon, Edward took the reins. On the hill near Mount Pleasant farm (Mr Barnwell’s place), the horses took fright when “a gentleman passed them on horseback” and galloped down the hill. “{Edward} held on to the traces of the body horse to keep up with them. When he got to the foot of the hill the horse trampled upon him when he fell, and the wheels passed over him”. Edward was taken home on a passing cart. He was visited by the surgeon from Wolston, Dr George James Thurston, who had replaced John Calvert Blanchard who, readers may recall, had carried out the post mortem on Elizabeth Hirons. He had suffered internal injuries apparently arising through a wound in the groin, “apparently done by a nail or shoe of a horse” and was in great pain. Mr Thurston states, “He gradually got worse and on the Wednesday (i e 15th March) I told his mother that nothing could save him. I left it to her to tell him.” Behind those two laconic and factual sentences lies a world of pathos. Edward passed away on Monday 20th March. The Coroner put the legal points to the jury. He advised them that it was their duty to address the evidence. The issue was whether or not it was reasonable for Mr Spencer to regard Edward Hunt as being fully competent to take charge of the team. If Edward should not have been so regarded then it was culpable negligence on Mr Spencer’s part and would attract a verdict of “manslaughter”. If it was right that he should be seen as fully competent then it would be “accidental death”. An interesting exchange between the Foreman of the Jury and the Coroner is recorded. The Foreman said that “he (i e the Foreman), had sent his team to Coventry that day with a load of wheat and he would be bound that on his return, the man would ride and leave the boy to drive home”. In essence he was identifying what was the normal practice. The Coroner, who seems here to be addressing the evidence himself, said “he had no doubt but that the boy’s death was caused by the wagoner”. Having deliberated, the jury returned a verdict of “Accidental Death”. Truly a tragic and difficult case and despite the barrier of time one can but empathise with how William and Sarah Hunt felt in that March of long ago.

Frank Hartley