At the bottom of this page is a timeline reflecting the “Village School in Wartime”, aligned with other wartime events.

The threat of war increased during the late 1930s, with the Munich Crisis in 1938 heightening awareness, and even with the apparently positive outcome on 30th September 1938 – “Peace for our Time”, preparations for a possible conflict continued.

Evacuation Planning

One specific initiative that would involve the two villages was the need to find safe havens should various cities come under attack from the air for those not involved in the conflict, either directly or in support – notably children.

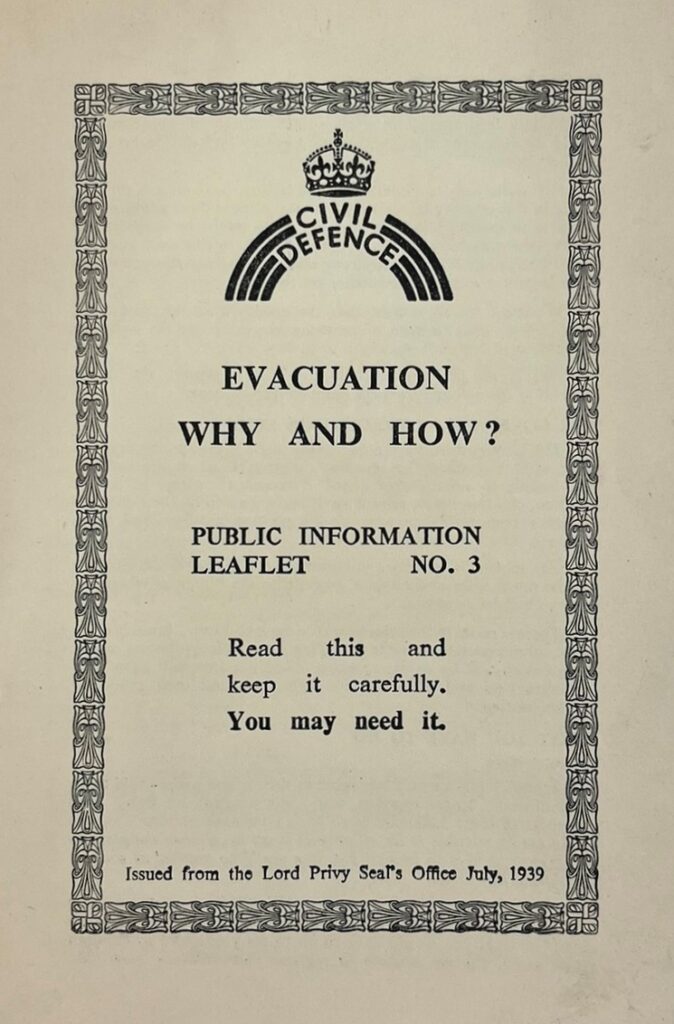

In order to be able to evacuate large numbers careful planning was required, and this proceeded in earnest during 1939 (war was not declared until 3rd September).

In Warwickshire there were two areas designated for evacuation – Birmingham and Coventry (with Smethwick in Staffordshire also grouped into the discussions). Coventry wasn’t included in the original Government July 1939 plan and associated leaflet, but was included shortly afterwards. There was also the wider need for London Evacuation.

Three districts were designated “neutral” which meant there was doubt whether they might be targeted, and so no evacuees were to be sent there – these were Nuneaton, Sutton Coldfield and Bedworth.

Rugby Borough, including both the town area and the rural area was, along with Shipston-on-Stour the only Warwickshire area planned to receive evacuees from London, along with evacuees from the other designated areas in Warwickshire.

The remaining boroughs (Leamington, Stratford, Warwick, Kenilworth, Solihull, plus the rural districts of Alcester, Atherstone, Meriden, Southam, Stratford(rural), Tamworth and Warwick(rural) were to receive evacuees from Birmingham, Coventry and Smethwick.

The areas earmarked to receive evacuees were then tasked with surveying the towns and villages in their area to establish how many evacuees they could take. This meant the appointment of “visitors” who would be tasked with visiting each home in their designated area to log the evalution possibilities. For each property they were to log and / or assess:

- The Number of Habitable Rooms

- The Number of Persons Ordinarily Resident

- Possible number of Persons That Can Be Accommodated

This information was logged on a form that was then used to record the actual numbers of people allocated to that address, and requirements such as additional bedding.

A billeting officer was appointed for the area, with wide-ranging responsibilities.

Operation Pied Piper

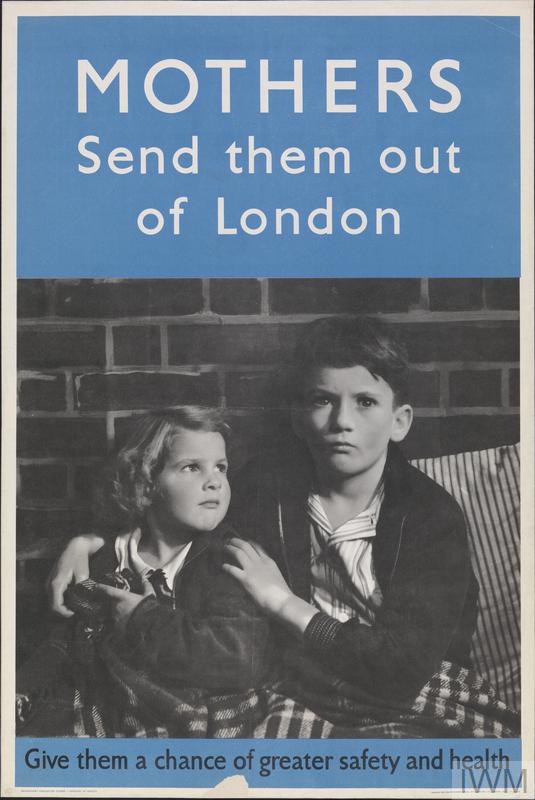

As early as September 1st 1939, two days before war was actually declared, the decision was made to start evacuations from areas of London seen as the most vulnerable. Once the Nazis had invaded Poland it was time to put a plan in place that had been put in place some while before, and Operation Pied Piper saw groups of children assembled in London to be sent off to destinations seen as safe from the imminent war. The children had their gas marks, a small ration supply, a small bag or suitcase with a few clothers, plus a name tag

For the villages around Rugby, including Dunchurch, Brinklow and Church Lawford, a contingent was sent from Willesden in North London, accompanied by their teachers. The group were loaded onto a train that would take them to Rugby, and from there they were loaded onto buses to take them to their pre-determined destination. For Church Lawford a party of 47 evacuees arrived along with 3 teachers arrived on September 2nd, the day before war was declared. They were met by local people and transferred to the various homes that were known as their billets.

The children were hosted in various family homes, including some in Bretford who joined others from there at school in Church Lawford. Wherever possible siblings were kept together, with farms often taking the bigger groups.

Other local villages took evacuees from other parts of London – for example Wolston took people from Islington and Ealing, whereas Harborough Magna and Churchover took them from Stoke Newington. Rugby itself acted as a focus point to receive and allocate the evacuees, but at this stage did not directly take the initial refugees.

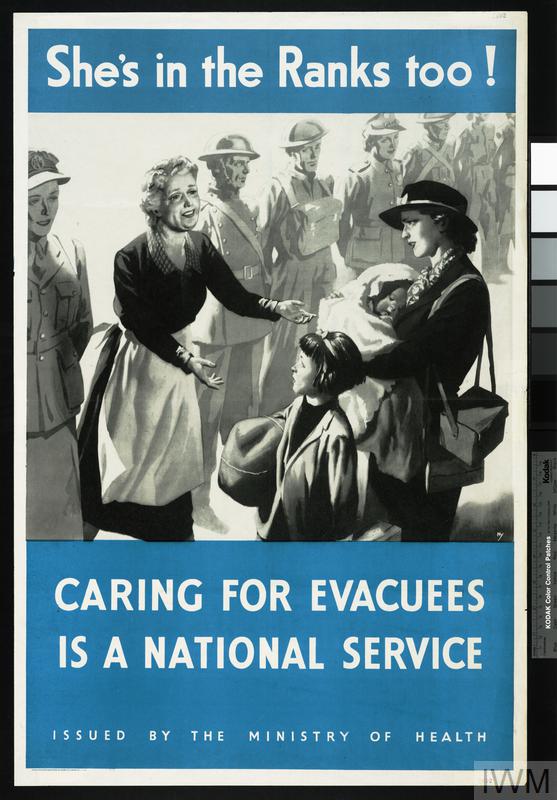

The Image: IWM (Art.IWM PST 0076) shown has been made available by the Imperial War Museum for “Use on websites that are primarily information-led, research-oriented and not behind a paywall.”

Education in Wartime

With the war declared on September 3rd schools were closed for a week, so it was September 11th before schooling was provided. In the first instance, in what was agreed to be a temporary arrangement, the school was used in the morning for the evacuees, and in the afternoon for the local children. There was always a desire to get the total of 114 children (67 current pupils plus 47 evacuees) into mixed classes, being taught by both the local and incoming teachers, and initial amalgamation was planned during the first fortnight, with the rector agreeing that a room in the rectory could be used to provide extra space for the more senior evacuees, so that the junior and infant classes could be accommodated in the school. The use of the Rectory Room was delayed whilst permission was sought from the local authority to do this.

At this time the school leaving age was 14, although some children went to places to schools in Rugby aged 11, and stayed on at school for longer. Those who stayed at the village school were allowed to spend time working on farms from the age of 12 for various activities including Potato Picking.

The village school was instrumental in the evacuation plans for the two villages, and headmistress “Miss Meikle” had a key role for the first 18 months of this period before she left to be married – many will remember her as Janet Wotherspoon, who was involved in village life for many years after the war. The plan even allowed for the school caretaker to be paid extra to facilitate the extra hours and numbers. Extra furniture was also acquired, along with more books and needlecraft items.

During the early days of the War the National Registration act was passed and a National Register taken as detailed here. Some of the names of the Willesden Evacuees can be seen in the entries for the host families.

Another part of the process was that the local school welfare people helped to look after the needs of the evacuees – they had all been checked by the doctor during the first fortnight, with some also sent for eye checks at the hospital. Dental checks were carried out for all – as was the norm, The welfare team also did checks of both the Reading Room and Rectory Room as they both were used for lessons. Other checks included the obligatory checks for head lice – with a good report all around.

With the conflict underway there was an increased push to allow more children to help on the farms during the harvest seasons – as the elder children had done in the past, when the school would close for up to a fortnight. There was some resistance from the local authority to this in the first year, but it quickly became clear it was a necessary concession. Other instances were seen where children helped doing other jobs on farms where the usual labour force was depleted or insufficient. Although the agricultural labourer was seen as having a “reserved occupation”, helping to keep numbers up, the need for the country to become largely self-sufficient for food meant increased labour pressures on the farms.

The main school was now accommodating 85 pupils, with the remainder (the older evacuee girls) based in the Rectory. The attendance percentages during the initial period were excellent – they would tail off as the various winter bugs and weather issues came along.

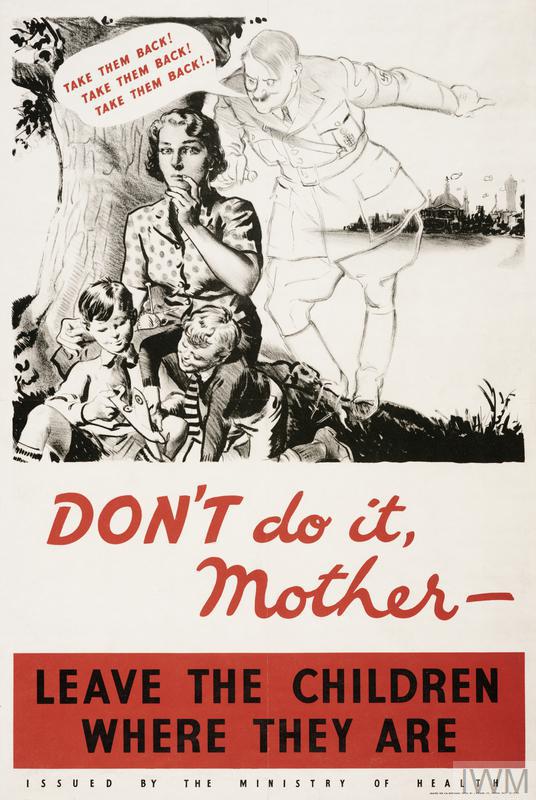

As spring 1940 approached the number of evacuees had declined, affected by what became known as the “phoney war”, with little or no bombing having occurred in those first 6 months of the war, so families were bringing their children back to London – something that was discouraged as shown by the poster on the right. By March 1940 half of the Willesden evacuees had left the local area, and after Easter that year the 20 remaining were to be fully merged such that the 85 children in total could be accommodated without the need for the room at the Rectory. However the Willesden staff wished their senior girls to remain at the Rectory, so this was provided for. The number slipped by a further seven by mid April, but at that time the school was being prepared for the possibility of further evacuees from the East Coast, and as a refuge should bombing occur in nearby towns (sheltering up to 200 local refugees and hosting a feeding station for a further 250).

It was noted that the local hosts were expected to pay expenses such as bus fares to secondary schools such as Westlands – and in other cases the hosts offered to provide shelter if the evacuee declined a request to return home.

The Image: IWM (Art.IWM PST 3095) shown has been made available by the Imperial War Museum for “Use on websites that are primarily information-led, research-oriented and not behind a paywall.”

A further challenge came towards the end of the summer term in 1940, with two local children and three of the refugee children being considered for evacuation overseas. The final Willesden teacher returned to London at the end of the summer term, and all children were to be accommodated in the main school. During the summer break the school remained open to the junior children for recreation rather than direct education, with the school milk scheme continuing over the break.

The Coventry Blitz

By the end of the summer break in 1940 the threat from air raids was much increased so rest periods during the day were introduced for the children. The senior children were able to help with the potato harvest as they had done before the war.

In November 1940 the Coventry Blitz meant the villages accommodated evacuees from Coventry, with 18 arriving by November 22nd. Their schooling was carried out in the Reading Room assisted by a teacher from Coventry. Many other refugees from the Coventry devastation were accommodated in different ways – some Coventry families sheltered locally but returned to the city during the day for work and school purposes.

Details of how the Coventry Evacuees were received in King’s Newnham can be found in Liz Parvin’s article here. It might also be noted that one family from Coventry – the Deverell family – remained in King’s Newnham after the war and integrated into the parish with

Establishing other Local Information During Wartime

The concept that “careless talk cost lives” was well understood during wartime, and this meant that far fewer records were kept, and few village events were covered in the local press.

The Wolston Group details how further evacuees were taken from London during 1940 and 1941 as the blitz period meant many homes there were destroyed – including from Forest Gate and Islington. Quite whether any of those additional evacuees were housed in Church Lawford or King’s Newnham in addition to the Willesden evacuees isn’t too clear, although there is no reference to this in the school records. By late 1940 the focus was on the Coventry refugees and evacuees.

As can be seen in the timeline below, there were various incidents during the war that resulted in further evacuations, the provision of temporary shelter or other supporting resources.

The story of one of the Willesden Evacuees was featured in a series produced by the BBC in 2005 – link here. Although the references are mostly to time spent in Brinklow, there is a local link as Frank was married at St Peters, Church Lawford to Brenda Ingram. This and other recollections of evacuees are on the OurWarwickshire site, indexed here.

The link above also links to stories from the evacuees of the Coventry Blitz, with reference to Eathorpe and perhaps a similar village situation – the initial link is here. Details of support for victims of the Coventry blitz from King’s Newnham are here.

The Image: IWM (Art.IWM PST 15094) shown has been made available by the Imperial War Museum for “Use on websites that are primarily information-led, research-oriented and not behind a paywall.”

The school also participated in the various campaigns organised to assist others during wartime. This ranged from food cultivation and wild fruit gathering (blackberrying), as also discussed on the OurWarwickshire website here, collection of foil and paper, and various savings schemes, such as the Red Cross Prisoners of War Fund. Another focus for the school as well as the villages as a whole was the National Salvage Drive, championed by the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service. One part of the campaign to save and reuse materials was the “Book Drive” to salvage and reuse paper – in one week the schoolchildren in the two villages collected almost 3500 books.

Information for this archive entry has been obtained from the Warwick Records Centre and Rugby Library, including the school log, with specific reference to the book “Village School in Wartime” by David Howe. A further resource has been from published books, including: “Wartime Britain 1939-1945” by Juliet Gardiner, “Warwickshire Schools and the Second World War” by David Howe and “A Boy’s Own Story” by Brian Scoggins (which records a wartime evacuee’s experiences).

| Date | Event |

| 30/9/1938 | Munich Agreement – “..Peace for Our Time.” |

| March 1939 onwards | Britain Rearms and Prepares for War – including Evacuation Preparations |

| 01/09/1939 | Operation “Pied Piper” begins |

| 02/09/1939 | Willesden Evacuees Arrive 47 children and 3 teachers |

| 03/09/1939 | War Declared – Village School Closed |

| 11/09/1939 | Village School Reopened (85 pupils main school, 19 in a room in the rectory) |

| Autumn 1939 | Dig For Victory Campaign Launched |

| 25/09/1939 | Petrol Rationing Introduced |

| Sep-1939 to May 1940 | Phoney War Period – Many evacuees return home (Only 21 of 47 Evacuees left by early 1940, 13 by April 1940) |

| 08/01/1940 | Food Rationing Introduced (Butter 4oz, Sugar 12oz, Bacon / Ham 4oz per week) |

| 11/03/1940 | General Meat Rationing Introduced (value of 1s10d per person per week) |

| 14/05/1940 | Gas Masks To be Carried |

| 31/05/1940 | School on standby to be distribution centre for East Coast Evacuees, and as a refugees centre for up to 200 from local towns – plus further 250 in feeding centre |

| 02/06/1940 | Local Troops return From Dunkirk (Evacuation began 26/5/1940) |

| 10/7- 31/10/1940 | Battle of Britain |

| 7/9/1940- 11/5/1941 | The London Blitz |

| Aug 1940-Oct 1940 | Initial Coventry Bombing Raids |

| 14-15/11/1940 | Coventry Blitz – 4300 homes destroyed |

| 22/11/1940 | 18 Official Evacuees Arrived From Coventry – From South Street School |

| 24/12/1940 | School remains open over Christmas holiday to help families with additional heads |

| 28/02/1941 | Absences due to the need to shop for clothes etc during the week to avoid overcrowded buses. |

| 31/03/1941 | Official Evacuee numbers low – 2 Willesden, 8 Coventry, 2 Clifton Transfers (ex-Coventry) |

| 22/04/1941 | Total Evacuees in school 25 |

| 08-11/04/1941 | Further Major Air Raids on Coventry |

| 01/05/1941 | Mrs Stocking Takes over as Head of School |

| 01/06/1941 | RAF Church Lawford becomes operational |

| 01/06/1941 | Clothes Rationing Introduced |

| 01/10/1941 | Potato Picking Closure (12 year olds plus) |

| 01/03/1942 | Air Raid Shelter set up in Church Lawford |

| 01/08/1942 | Bread Supply Limited to the “National Loaf” |

| 03/08/1942 | Last Major Raid on Coventry – with more evacuees and overnight hosting |

| 06/06/1944 | D-Day Landings |

| 08/09/1944 | V-2 Flying Bombs Reach UK |

| 08/05/1945 | VE Day |

| 15/08/1945 | VJ Day |

| 21/07/1946 | Bread Rationing Introduced |

| 25/07/1948 | Flour / Bread Rationing Ended |

| 19/05/1950 | Petrol Rationing Ended |

| 15/03/1949 | Clothes Rationing Ended |

| 04/07/1954 | Food Rationing Ended |